ZJU scientists discover the mystery of watermelon cracking

Fruit cracking is episodic in nature, associated with a suite of physiological, biochemical, environmental, cultural, anatomical and genetic factors. Evolutionally speaking, the “ripening of the melon” helps seed dispersal and plant proliferation, but industrially speaking, fruit cracking reduces economic benefits and consumption values tremendously.

Rind hardness or cracking resistance is intimately bound up with pulp quality. Therefore, one of the aims in watermelon breeding is to produce a type of watermelon marked by both the hard, cracking-resistant rind and the crisp and tasty pulp. In this way, it will become a one-size-fits-all solution for farmers, dealers and consumers.

Prof. ZHANG Mingfang from the Zhejiang University College of Agriculture and Biotechnology led his research into a particular gene related to cracking resistance in fresh fruits, which not only provides new insights into the mechanism for cracking resistance, but also helps accelerate the targeted breeding of cracking-resistance varieties. The research findings are published as a cover article in Plant Biotechnology Journal.

One of the highlights in this research is to mark cracking resistance capacity with numerical data. The research team led by ZHANG Mingfang used a texture analyzer to assess 8 different indicators, such as rind hardness, cracking resistance, cracking rate and cracking work etc. “Precisely quantifying cracking resistance capacity and accurately anchoring the candidate gene for rind hardness are of immense scientific significance in providing crucial theoretical support for cultivating a cracking-resistant breed of watermelon,” said ZHANG Mingfang.

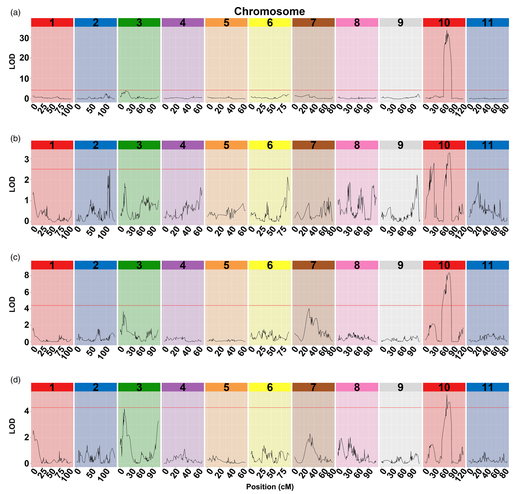

ZHANG Mingfang et al. also engaged in research into over 400 watermelons in the F2 population. After sequencing 11 recombinants in 159 F2 individuals, they found that all of the cracking-related indices are positioned on chromosome 10 and the region marked by rind hardness is the most salient.

Colocation of rind hardness parameters and cracking‐related traits. (a) RH (rind hardness), (b) CRN (cracking or not), (c) CRW (cracking work), (d) CRT (cracking time).

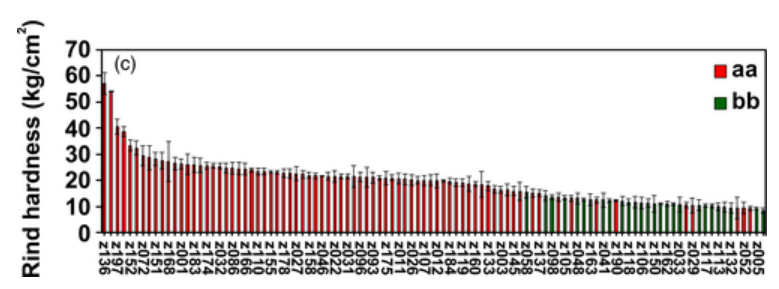

With the assistance of resequencing and KASP markers, researchers efficiently identified recombinants in F2 and F3 populations that contain homozygous domains on the target region. Inspection of the genotypic and phenotypic data from the recombinant F3 population zoomed the target region into a 9372 bp fragment, where they successfully identified an ethylene-responsive transcription factor 4 (ClERF4) as a rind hardness regulator. Taken together, haplotype analysis is an effective strategy to perform the fine mapping of traits associated with genes underlying qualitative and near qualitative traits.

The rind hardness and genotype of the 104 germplasm accessions

Ethylene is one of the most important hormones in plants, and it drives fruit ripening. The ripening process of climacteric fruit is accompanied by a peak in ethylene production and thus results in a dramatic decrease in fruit hardness. ERFs, signal factors that bridge internal and external signals and ethylene response, play important roles in stress responses, growth and development and senescence.

This study provides valuable insights into the underlying mechanism of rind hardness and fruit cracking resistance. These results will further enable the molecular manipulation of the desirable trait of fruit cracking resistance in fresh fruits such as watermelon via precise targeting of the causative gene ClERF4, which is relevant to rind hardness.