Dialogue@ZJU: With Prof. BAI Qianshen about Chinese calligraphy

[Message from the Editor: Chinese calligraphy holds important position in Chinese culture. Recently Prof. BAI Qianshen, an art historian of calligraphy, a calligrapher, dean of the School of Art and Archeaology and director of ZJUMAA, told us his experiences in teaching calligraphy in the US and the stories about his monograph Fu Shan's World: The Transformation of Chinese Calligraphy in the Seventeenth-Century.]

Q1:What are the biggest challenges you faced when you taught calligraphy in the United States?

I have been teaching Chinese calligraphy in the United States for 20 years, before joining Zhejiang University in 2015. Calligraphy is a term we use for describing or naming the art of Chinese writing. The writing tool is a brush made of animal hair with a pointed end which is very sensitive to the surface of paper. But in the West, calligraphy is the craft of writing, not a fine art, so it does not enjoy such a social status and aesthetic qualities. In major universities, there is no one single Western art historian who studies Western calligraphy. Actually, there is no equivalent art. It is very difficult for Westerners to understand this art. This is the first challenge.

The second challenge is to figure out what kind of language to use to describe and analyze this art form. Calligraphy was a form for self-expression and social communication. First, writing was important. As it was hard for people in different regions of the empire to understand each other's dialects, writing helped unify the entire empire. Second, neighboring countries like Japan, Korea, and Vietnam use Chinese characters. This symbolic writing system goes beyond borders. Third, paperwork was the essence of the bureaucratic system. In the past, all government officials and emperors across dynasties practiced calligraphy. In their practice of brush writing, they gradually developed very rich artistic vocabularies. Here I would like to borrow the German scholar Lothar Ledderose's words: "Calligraphy is the art of the elite".

Then the question comes. For people who have never had any experience of the Chinese brush, how can you communicate to them the charm and the appeal of Chinese calligraphy? I developed a method to approach the Western audience step by step. First in easy and simple language I paved the ground by giving some introduction through lectures on the role of Chinese calligraphy, the structure of the brush, and the nature of the Chinese writing system. Then I showed them the strokes and techniques. Eventually I discussed the stylistic evolution triggered by either the artist's self-conscious pursuit or external social factors.

Q2:What is the status of calligraphy in our everyday life now?

In the past, calligraphy played an important role in the Civil Service Examinations (both at the provincial and palatial levels) so it was closely related to the everyday life of high officials and elite. A new education system was introduced into China with the abolition of the Civil Service Examinations in the early 20th century. There is no requirement for calligraphy in the gaokao (college entrance examinations). In the present era, efficiency is important. People use pens, pencils, and computers instead of brushes. Nowadays, many people love calligraphy as a traditional art and some still practice it, but it is no longer an art of elite.

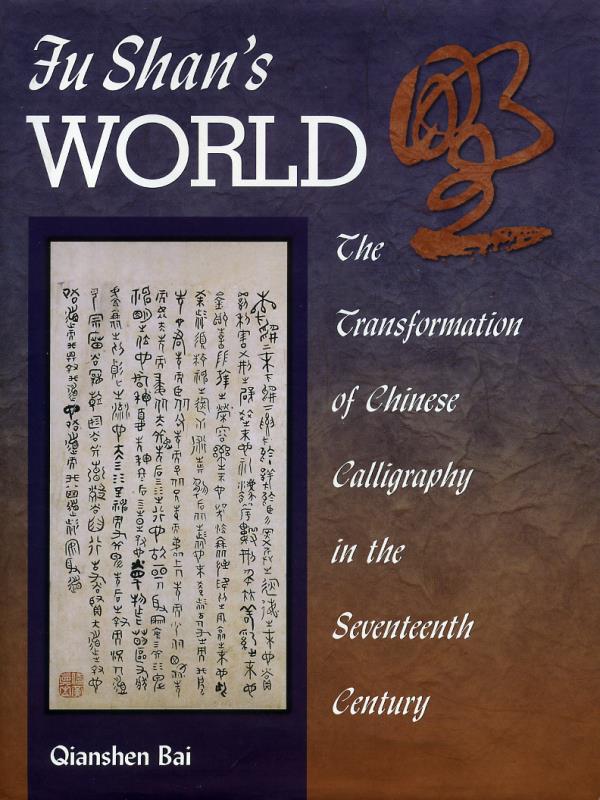

Q3:Your monograph Fu Shan's World: The Transformation of Chinese Calligraphy in the Seventeenth-Century has been widely acclaimed as "one of the most successful studies of a single Chinese artist ever written." How do you form a holistic picture of the forest while focusing on one tree?

Western art history mostly adopts case study as the basic method, which sometimes can be very narrow. In the study of Fu Shan, my approach was focusing on this individual artist while putting him in a broader context. Fu Shan lived in the transitional period from the Ming to the Qing Dynasty when there were many complicated and intertwined social issues. Through the discussion, I wanted to explore different schools and how they evolved into one of the major schools in the Qing Dynasty, i.e., the stele school of calligraphy emerging as a challenge to the traditional Chinese calligraphy canons, the so-called copy book traditions.

Fortunately, a whole collection of Fu Shan was published in the year when I was going to write my dissertation. I collected first-hand information by visiting museums and libraries. I dug into his life with many details, including his relationship with other artists, his social network, and his attitude toward the Qing government and the officials who worked for the Manchus. I also delved into his artworks across time and hence his stylistic evolution. When I discussed this particular artist, Fu Shan, in a wide social context; I focused on a tree without abandoning the forest. First, you have to know the tree very well. Then you need think big, and ask big questions. And you keep going into the tree and out to see the forest, and repeat this in-and-out process to see the relationship between this tree and other trees and the location of this tree in the big forest. At the end of the day, a detailed account of Fu Shan's life was provided, and meanwhile questions related to his living period were answered.

Related Stories: