ZJU scientists discover the positive buffering effect of forest edges on plant-pollinator networks in face of declining forest area

The decline of insect pollinators has captured immense attention worldwide. Popular notion has it that habitat fragmentation and ecosystem decay exacerbate the decline of insect pollinators due to habitat loss. However, the study conducted by Prof. DING Ping’s team at the Zhejiang University College of Life Sciences found that in forest ecosystems, open sunny forest edges are able to support more floral resources and pollinators than the dark interior within closed-canopy forests, leading to the positive effect of forest edges. This stands in sharp contrast with the conventional narrative that edge effects often aggravate the negative effects of habitat loss on biodiversity, primarily because most studies on the effects of habitat fragmentation on plant-pollinator communities focus on open-habitat systems such as grasslands or croplands where edge effects are probably negative or neutral.

The study was published in a research article titled “Forest edges increase pollinator network robustness to extinction with declining area” in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution on January 31.

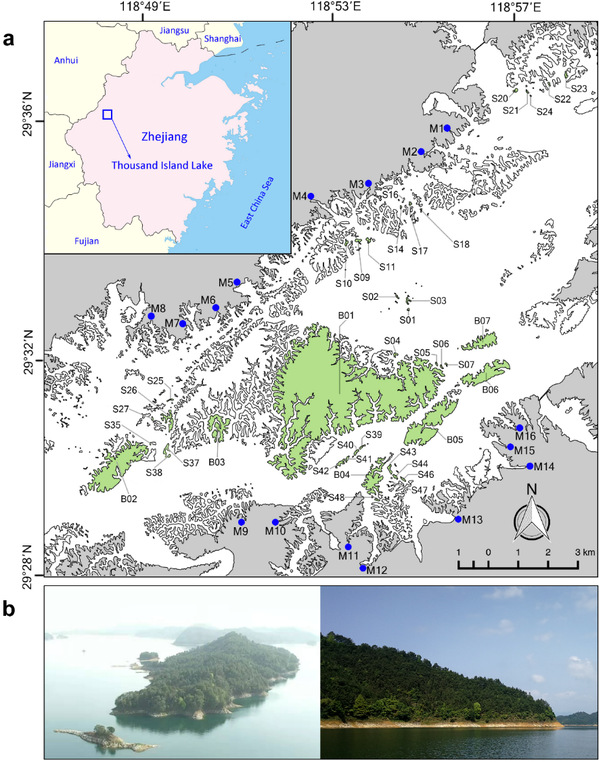

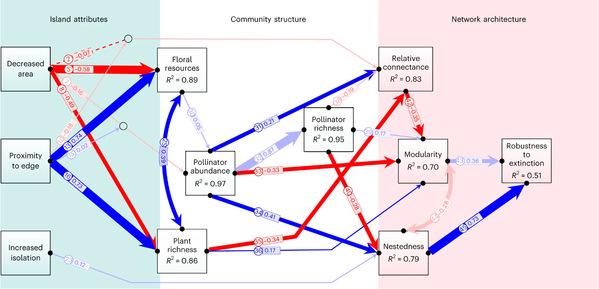

In a fragmented land-bridge island system at the Thousand Island Lake, this study recorded about 20,000 plant-pollinator interactions on 41 islands and 16 mainland sites over three years. Using structural equation models, DING Ping et al. found that floral resources, pollinator abundance, and plant/pollinator richness at forest edges are about tenfold higher than in the interior. Edge networks contain highly specialized species, maintaining high robustness to extinction instead of exacerbating the adverse effect of forest loss on networks and thereby reducing the collapse risk of plant-pollinator networks.

Fig. 1: Study site locations. a. The 41 study islands (green shading; B01–B07, S01–S48) and the 16 mainland sampling sites (grey shading and blue dots; M1–M16) at the Thousand Island Lake, Zhejiang Province, eastern China (partially reproduced from Ren et al.). b. The topography at the study site is mountainous, and flooding of the valley produced complex island shapes. Photo credits: P.R.

Fig.2: Generalized multilevel SEM showing the direct and indirect pathways through which forest fragmentation influences plant-pollinator community structure and network architecture.

Anthropogenic edge effects are often thought to exacerbate the negative effects of forest loss on pollinators, but this study showed that forest edges not only attenuate the response to declining patch areas but also utterly reverse this negative effect. In continuous primary forests, natural forest gap-phase dynamics provide ample space and resources for light-loving species, and sunny forest gaps support a rich diversity of secondary species, thus contributing to more floral resources. However, forest gaps are relatively rare in secondary forests, so the role of the forest gap-phase dynamics is smaller due to higher coverage. Habitat fragmentation increases patch openness, and forest edges may play a similar role to natural forest gap-phase dynamics, which in turn may produce positive effects on plants and pollinators. This study attests to the positive role of forest edges in fragmented secondary forests.

From the perspective of biological conservation, this study is of considerable significance to large-scale reforestation programs in China and other parts of the world. If these reforestation programs can take into consideration the heterogeneity of forest edges and the dynamics of forest gaps, it will lead to greater benefits in these forest areas. It should be noteworthy that this study does not advocate that habitat fragmentation is good for biodiversity in a general sense. Instead, it suggests that protecting forest edges is effective in enhancing the heterogeneity of forest gap structures and the diversity of floral resources in the absence of effective restoration strategies, and that forest edges may play an unexpectedly positive role in network resilience, at least in the early stages of forest restoration.