Scientists uncover hidden microbial process linking sulfur and iron

A team of scientists led by Dr. CHEN Songcan from the College of Environmental and Resource Sciences at Zhejiang University has discovered that microbes can power their growth by linking two key chemical reactions—sulfide oxidation and iron reduction—processes previously thought to occur only through non-living chemistry.

The study, conducted in collaboration with the University of Vienna (Austria) and the Ningbo Observation and Research Station of the CAS Institute of Urban Environment, was recently published in the prestigious journal Nature. Dr. CHEN is both the lead author and co-corresponding author of the paper.

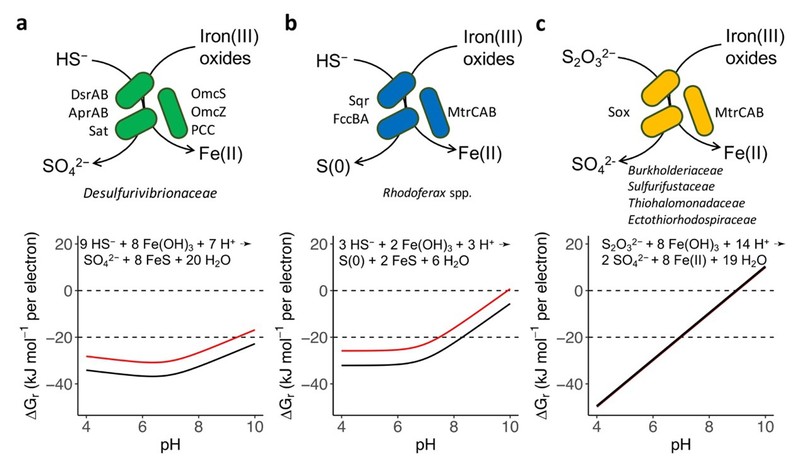

For decades, scientists have recognized that sulfur and iron are central players in the biogeochemistry of our planet. The cycling of sulfur, in particular, underpins ecosystems both on land and in the oceans, with impacts extending from the global carbon cycle to climate change. Yet, one puzzle remained unsolved: how does sulfide, which is a common product of microbial sulfate reduction, get re-oxidized back into sulfate, especially in environments where oxygen are absent?

“Pure culture environments have shown that microbes can oxidize sulfide using oxydants like oxygen, nitrate, or manganese oxides,” said Dr. CHEN. “But in many environments devoid of these recognized oxidants, sulfide still disappears with quantitative sulfate formation, something we couldn’t fully explain.”

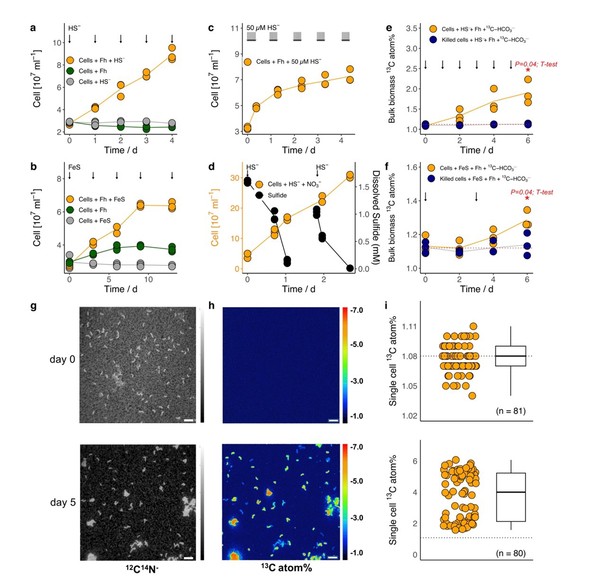

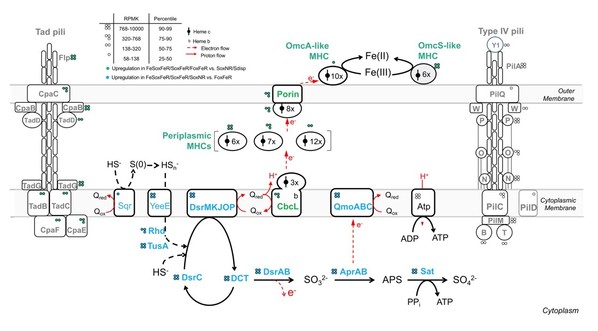

To crack this code, Dr. CHEN’s team analyzed vast genomic datasets. They found that genes responsible for sulfur oxidation and iron reduction appeared together across diverse microbial phyla, a strong sign that the coupled sulfur and iron metabolism is widespread.

What’s more, close relatives of D. alkaliphilus, with similar genetic makeup, appear to be abundant in environments ranging from marine sediments and hydrothermal vents to soils and freshwater wetlands. This suggests that the hidden sulfur-iron link may be far more common than previously imagined.

“This discovery gives us a new lens to view the ‘cryptic’ sulfur oxidation that happens in many oxygen-free, iron-rich ecosystems,” said Dr. CHEN. “It reshapes how we understand the sulfur and iron cycles on the Earth, and how they connect with other elemental cycles.”

The work not only challenges long-held assumptions but also adds a new dimension to the enigma of how microbes drive the planet’s biogeochemistry, even in the darkest, oxygen starved corners of the Earth.

Adapted and translated from the article by ZHOU Wei, ZHA Meng

Translator: FANG Fumin

Photos by ZHE yin

Editors: HE Jiawen, ZHU Ziyu