ZJU’s “slipknot” research featured in Nature: a single suture tackles the global challenge of surgical “force blindness”

In Chinese tradition, a “knot” embodies both practical know-how and deep philosophical meaning. Today, that ancient wisdom has inspired a scientific leap at Zhejiang University (ZJU), one that promises to solve a long-standing global challenge in minimally invasive surgery: the loss of tactile sensation, often described as “force blindness.”

A multidisciplinary ZJU team has developed a simple yet ingenious solution—a slipknot-based structure that restores force perception without electronics. Their study, titled “Slipknot-gauged mechanical transmission and robotic operation,” was published in the journal of Nature on November 27, capturing wide attention in scientific academia both home and abroad.

In traditional open surgery, surgeons rely on their hands to feel tissue properties and gauge suture tension. But as procedures have shifted toward minimally invasive and robot-assisted surgeries, trauma has decreased while tactile feedback has all but vanished.

“Technology is advancing, but the surgeon’s tactile sense is fading,” said CAI Xiujun from Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine. Having led the shift from open to minimally invasive surgery, he knows the challenge all too well: without tactile cues, surgeons must estimate the correct tightness of a knot purely by experience.

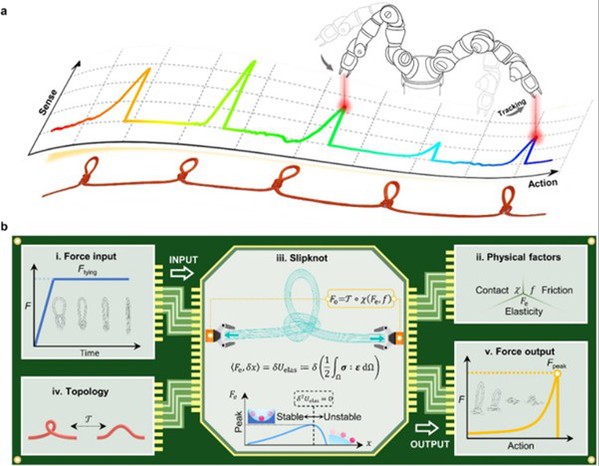

The process of mechanical information writing and reading in a slipknot.

Clinically, the commonly used “surgeon’s knot” is a fixed knot that cannot be adjusted once Traditional surgical knots are fixed and cannot be adjusted once tightened. Too little tension can cause leakage; too much can cut into tissues. While force sensors exist, they pose a severe challenge to sterilization and integration, thereby limiting their clinical use.

The breakthrough emerged unexpectedly during a cross-disciplinary discussion, where mechanics researchers and clinicians were brainstorming.

“Why not just tie a slipknot beside it?” This seemingly casual remark, voiced almost instinctively by Dr. YANG Xuxu from the Center for X Mechanics, Zhejiang University planted the seed for a transformative idea.

Despite its simplicity, the slipknot functions as a finely tuned mechanical gauge. When the suture is pulled, the slipknot releases at a predetermined threshold, sending a sharp force peak along the thread to the fixed knot. The moment it “sacrifices” itself and opens becomes a mechanical signal: “The force is just right—lock the knot now!”

As Professor LI Tiefeng from the Center for X Mechanics, Zhejiang University explained, the slipknot stores a precise peak force as mechanical “information” during its formation. When it releases, that information travels through the suture can be captured by robotic or visual systems, laying a foundation for precise force control.

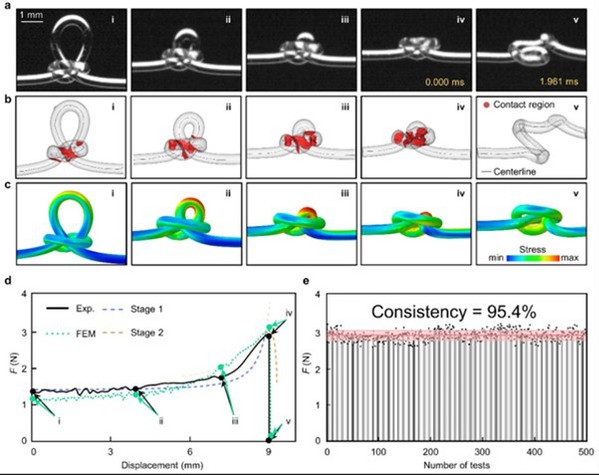

Turning this flash of inspiration into a reliable surgical tool entailed ensuring that each slipknot opens at a predictable, consistent force. Using high-speed cameras, micro-CT imaging, mechanical modeling, and finite-element simulations, the team identified the governing principles: the release force correlates with the pre-tension applied when tying, number of loops, diameter, friction coefficient, and material modulus.

Mechanical modelling and characterization of slipknots.

“With these parameters, we can engineer slipknots that release at designed forces,” the researchers noted. Experiments confirmed that well-designed slipknots exhibit highly stable, repeatable force thresholds.

The result is “Sliputure,” an intelligent, force-calibrated suture that encodes mechanical information directly into its structure, no electronics required.

In animal experiments, including open rat colonic repair, laparoscopic porcine colonic repair, and robot-assisted surgeries, Sliputure consistently produced optimal anastomosis: tight enough to prevent leakage but gentle enough to avoid tissue damage.

When integrated into surgical robots, the system can detect the instant the slipknot opens through visual cues and automatically halt instrument movement, achieving millisecond-level responsiveness and completing a “sense–feedback–brake” control loop.

Slipknot gauges mechanical transmission in surgical operations.

The achievement is a fitting testament to ZJU’s innovation ecosystem linking medicine and engineering. Professor YANG Wei, a pioneer of solid mechanics, emphasized that such cross-field integration often leads to entirely new principles and technologies in robotics and biomedicine.

According to CAI Xiujun, the system dramatically improves the consistency of knot-tying forces, enabling junior surgeons to approach the performance of veterans, which is a crucial step toward quantifiable force control in surgery.

Notably, the slipknot-based mechanism operates without complex electronic components, avoiding risks associated with power failure or signal loss. This means it can function reliably not only in deep surgical cavities but also in extreme environments such as deep sea, outer space, underground engineering, and even in micro-scale assembly.

The team is now building a force-value database for different tissues and developing product lines for robotic, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and neurosurgical applications.

From ancient knot-tying traditions to the frontiers of surgical robotics, from a serendipitous idea to a Nature cover story, the ZJU team has woven mechanical intelligence into a single strand of suture, opening up new avenues for the future of surgery.

Translator: FANG Fumin

Editor: HAN Xiao