ZJU team unveils a fast-charging “thermal battery,” published in Nature

Batteries power modern life. Yet not all batteries store electricity. Some store heat.

Long before lithium-ion batteries, humans already used thermal energy storage. Ancient ice cellars preserved ice for summer use, while modern water heaters store hot water for later demand. These are all early examples of what scientists now call thermal batteries, systems that store heat and release it when needed.

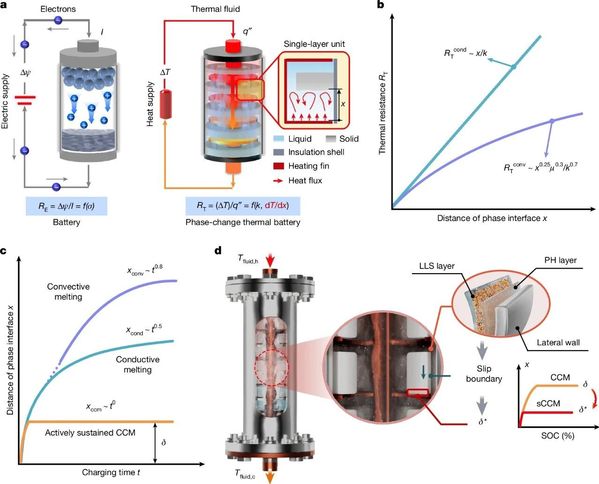

Among today’s most promising designs are phase-change thermal batteries, which store heat using materials such as paraffin, hydrated salts, or sugar alcohols. These materials absorb or release large amounts of heat as they change their phases between solid and liquid states. However, a long-standing trade-off has constrained their performance: materials that store heat efficiently tend to charge very slowly. Until now, engineers have struggled to achieve both high heat storage capacity and fast charging in the same system.

A research team led by Dr. FAN Liwu from the College of Energy Engineering at Zhejiang University, together with its collaborators, has found a way to address this trade-off. Their work, published on January 8 in Nature, introduces a new mechanism called “slip-enhanced close-contact melting (sCCM),” offering a practical path toward fast-charging thermal batteries.

“Phase-change materials (PCMs) can store a huge amount of heat in a very small volume,” FAN Liwu explained. “But they are usually poor at conducting heat, which makes charging painfully slow.”

Previous solutions have relied on adding highly conductive fillers to enhance heat transfer. While effective, these fillers take up valuable space, reducing energy capacity the thermal battery can store.Other approaches use external forces, such as pressure or magnetic force, to shorten heat transfer distance, but these methods consume additional energy and make large-scale operation difficult.

In conventional design, a solid PCM tends to stick to the container lateral wall, hindering the formation of the CCM. FAN Liwu’s team solved this by making the lateral wall of the thermal battery extremely slippery.

Fast charging of phase-change thermal batteries

With this composite surface, the solid PCM no longer clings to the wall. Under the gravity, it stays pressed against the heat source at the bottom, maintaining “close-contact” to the heated surface. Importantly, this strategy works with existing PCMs, for it does not require inventing new ones.

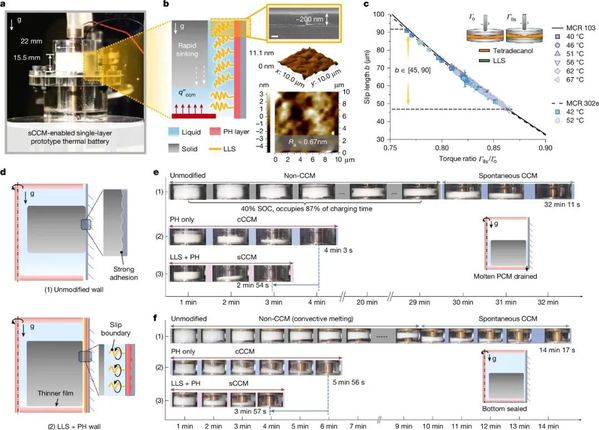

The idea is implemented through an all-solid composite surface made of two layers. The first is a pulse heating film that gently preheats the wall. This creates an ultra-thin liquid layer, about 40 micrometers thick, thinner than a human hair, between the lateral wall and the solid PCM. The second layer is a liquid-like surface with nanoscale smoothness, which drastically reduces friction.

FAN Liwu offers a simple analogy: “It’s like heating a pan coated with a super-smooth layer. When you put butter on it, the butter doesn’t stick, instead it slides and melts almost instantly.” As melting begins, gravity helps PCM sink further, squeezing the liquid layer even thinner and keeping high heat transfer rate throughout the charging process.

A comparison of the sliding performance of liquid PCMs on liquid-like surface versus unmodified surface

The outcome is a rare combination: high power density and high energy density at the same time.

In fast-charging tests using a conventional organic PCM, the thermal battery achieved a power density of 850 kW/m³, indicating charging rate, while maintaining an energy density of 31 kWh/m³, reflecting heat storage capacity. When paired with highly thermal-conductive composite PCM, the power density surged to 1100 kW/m³, while energy density remained as high as 27 kWh/m³, demonstrating that heat storage capacity was not sacrificed.

In other words, the thermal battery charges faster without giving up much of the energy it can hold.

The research draws on expertise from multiple fields and institutions. Other key contributions came from Ningbo University, where Dr. YE Yumin’s team developed the ultra-slippery coating, and from Princeton University, where Dr. HU Nan’s group provided support in micro flow modeling.

“The idea really took shape during a long, in-depth discussion,” FAN Liwu recalled. “Everyone brought something unique to the table.”

The technology is designed with real-world use in mind. According to LI Zirui, the paper’s lead author, the system can be retrofitted onto existing thermal energy storage equipment and adapted to different temperature ranges.

Potential applications include industrial waste-heat recovery, solar water heating, and thermal management for power electronics, areas where improving efficiency can significantly reduce energy costs and carbon emissions.

FAN Liwu’s approach to research is also reflected in how he mentors his students: encouraging them to dig into fundamental mechanisms rather than settling for surface-level results.

After the idea of “slip” emerged, the team built theoretical models to explain how friction and drag affect melting. Experiments confirmed that when the slip length becomes comparable to the thickness of the micro liquid film near the lateral wall, drag on the remaining solid PCMs markedly decreases. The theory and experiments ultimately came together in large-scale sealed thermal battery tests that demonstrated stable, fast charging.

sCCM-enabled fast-charging process

LI Zirui, who joined the team as an undergraduate about 10 years ago, described the process as a long-term commitment. “We didn’t know where it would lead,” he said. “But trust within the team kept us focused on the science.”

The researchers now plan to scale up the system, refine their understanding of heat-transfer mechanisms, and address durability and long-term cycling stability. Preliminary follow-up studies have already shown stable operation for tens of thousands of hours with an organic PCM, suggesting strong potential for industrial deployment.

“We hope this work injects vitality to global efforts in sustainable energy,” FAN Liwu said. “It also shows that fundamental research can still lead to practical breakthroughs.”

Source: Zhejiang University

Translator: FANG Fumin

Editor: HAN Xiao