ZJU’s "Albatross" went through typhoon's eyewall to capture critical measurement

When Typhoon Wutip roared across the western Pacific earlier this year, nearly every vessel gave the storm a wide berth. One didn’t. Driven by the same wind that powered the cyclone, , an unmanned sailing vehicle (USV) intentionally headed straight for its eye-and made it out the other side.

In June, a research team led by Professor LI Peiliang at Zhejiang University’s Ocean College accomplished a milestone in marine meteorology: their wind-powered USV, Albatross, successfully crossed the eyewall of Typhoon Wutip (Severe Tropical Storm) and transmitted continuous air-sea interface data from within the its eye. It was the first time a Chinese USV had achieved this feat, contributing valuable data to understand typhoon formation and intensification.

Built for the storm

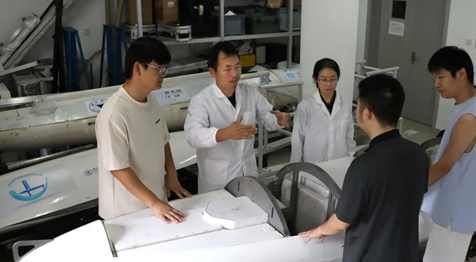

Albatross carries 2.5-meter sail and weights about 600kg. Albatross is equipped with sensors capable of measuring wind profiles, ocean currents, wave parameters, air pressure, etc.

Like the bird it’s named for, Albatross thrives on the wind. The sail adjusts dynamically to shifting gusts, optimizing lift and minimizing drag.the sail angle to generate pressure differences, it can glide efficiently through extreme conditions while conserving onboard energy for instrumentation.

Went through the eyewall

During TyphoonWutip, Albatross was deployed approximately 530 kilometers away from the storm’s eye. Over several tense days, LI's team monitored telemetry in real time from shore, as the vessel's advanced toward the eye of storm. At 00:28 on June 13, it went through the eyewall, encountering gusts up to 44 knots (about 81 km/h). Thirty minutes later, it emerged from the eye, fully operational and transmitting an uninterrupted stream of environmental data.

Despite advances in satellite, radar, and buoy networks, the tropical storm still required field observation within the eyewall for understanding how air-sea interaction affects typhoon intensity. The measurements of near-surface atmospheric and upper-ocean parameters are critical to calculate energy and momentum fluxes between the atmosphere and ocean outside and within typhoons.

Climate change further complicates the picture. As extreme and irregular events grow more frequent, conventional models struggle to account for new variables, eroding predictive accuracy. "Each new dataset from within a storm helps constrain our equations," LI explains. "It's the only way to see what's really happening at the interface between the sea and the sky."

Zhejiang University's Albatross helps fill that observational void. Its success not only demonstrates the resilience of wind-powered USV but also opens new possibilities for high-risk ocean monitoring-bringing scientists one step closer to decoding the inner life of typhoons.

Toward a global ocean observatory

Building on the success of the Wutip mission, LI’s team is now enhancing Albatross for global ocean observation. One upcoming missions will send the USV into the westerlies of the Southern Ocean, one of the planet’s most turbulent and least explored marine regions.

Future versions are being designed with diving capability to observe the air-sea transition zone, encompassing the upper ocean, air-sea interface, and marine atmospheric boundary layer. If achieved, the Albatross initiative could mark a new era in autonomous ocean observation— a fleet of sustainable, resilient platforms operating where human presence is impossible, expanding our understanding of Earth’s most dynamic waters.