ZJU team unveils breakthrough in needle-free insulin delivery

For the more than half a billion people living with diabetes worldwide, daily insulin injections are part of the routine — and part of the pain. Patients with Type 1 diabetes and many with advanced Type 2 diabetes rely on one to four shots a day, sometimes for life. Besides discomfort, injections may trigger side effects like hypoglycemia, all of which take a toll on long-term treatment and everyday quality of life.

A new study from Zhejiang University, published on November 20 in Nature, offers a disruptive alternative: insulin delivery through the skin, without needles.

The research team reports a newly designed, highly skin-permeable polymer called OP that can carry insulin through the skin and into the bloodstream. In animal tests, its insulin conjugate, called OP-I, lowered blood sugar just as effectively as traditional injections.

The work was led by scientists across Zhejiang University’s College of Chemical and Biological Engineering and School of Life Sciences, in collaboration with Imperial College London.

That’s why the Zhejiang University team was taken aback when earlier experiments revealed something distinctively unusual: the OP polymer, previously tested for delivering anticancer drugs into tumors, seemed to slip through tissues much more easily than expected.

“That led us to a simple question,” recalls Professor SHEN Youqing, who specializes in polymer-based drug delivery. “If OP can penetrate solid tumor tissue, could it also make its way through the skin?”

To their surprise, it could — and it did so with remarkably high efficiency, challenging the long-held assumption that large molecules are too bulky to cross the skin barrier.

Further inquiry revealed why OP behaves so differently. The human skin has a natural pH gradient: slightly acidic at the surface and neutral in deeper layers. OP takes advantage of this gradient by changing its charge as it travels downward.

At the skin surface (pH ~5), OP becomes positively charged and binds to negatively charged fatty acids — forming a temporary “reservoir” that builds up the concentration needed for penetration.

Deeper in the skin, where the environment is more neutral, OP switches to an uncharged, highly water-loving form. Freed from electrostatic interactions, it diffuses rapidly through the tiny gaps between cells.

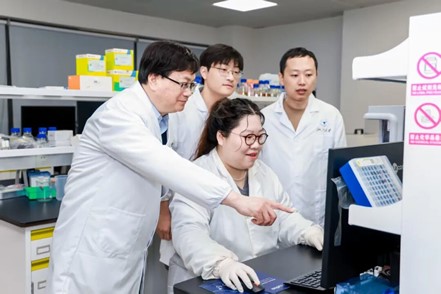

“It’s essentially a smart material that adapts to the skin’s chemistry as it moves,” said Professor ZHOU Ruhong, whose team used molecular-level simulations to map the process.

Molecular-level simulations of OP-I diffusion in the stratum corneum

The researchers then linked OP to insulin to create OP-I, which travels through the skin in a “hopping” motion along cell membranes — a route that protects insulin from being decomposed too early. Once through the deeper layers, it enters the bloodstream via lymphatic vessels.

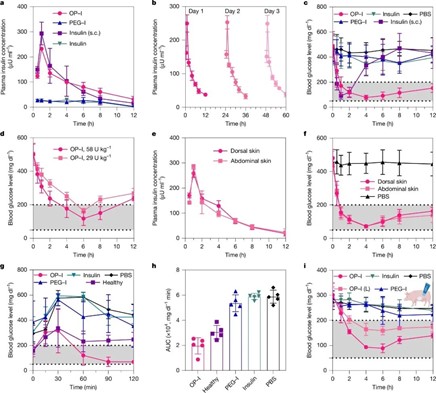

Testing in diabetic mice and mini pigs produced striking results. In mice, a single application of OP-I on the skin brought blood glucose levels back to normal within an hour. The effect lasted more than 12 hours without causing dangerous drops in blood sugar — a risk with standard injections. In mini pigs, whose skin is physiologically closer to human skin, a relatively low dose of OP-I was enough to normalize glucose levels.

Just as importantly, repeated use did no harm to the skin. The barrier remained intact, and no inflammation was observed — a significant edge over many chemical penetration enhancers, which often irritate or damage the skin.

Hypoglycaemic effect of topical OP–I in STZ-induced diabetic mice and minipigs

This means that, with successful clinical development, diabetes management could one day be as simple as applying a patch or cream. For many patients, “bidding farewell to needles” may finally become a dream come true.

The team believes the implications extend well beyond diabetes. Because OP can carry various biological molecules, researchers have already adapted the system for GLP-1 drugs like liraglutide and semaglutide, as well as therapeutic proteins, monoclonal antibodies, and siRNA.

“This is not just a one-drug solution,” Shen emphasized. “It opens up a new direction for delivering a whole class of biologic medicines through the skin, without injections.”

The technology has already been licensed to industry partners and is moving toward clinical translation. If successful, it could transform the way chronic diseases — including diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis — are treated around the world.

Translator: FANG Fumin

Editor: HAN Xiao