Discovering the soul of Chinese painting in 45 minutes

The lights dim, and a soft melody drifts through the classroom — Spring River in the Flower Moon Night. On the screen glows a scroll of misty mountains and winding rivers. For a moment, time bends. The twenty-first-century lecture hall fades away, and students at Zhejiang University find themselves standing beside the painters of the Tang and Song dynasties.

This is not a museum experience, but a class — “History of Chinese Painting”, taught by Associate Professor GAO Nianhua from the Department of Public Physical and Art Education. For her students, those 45-minute sessions open a window onto millennia of Chinese aesthetics, philosophy, and emotion.

Seeing the world through brush and ink

“Why should we study the history of painting today?” GAO often begins her first lecture with this question. Then she answers, quoting Tang-dynasty scholar ZHANG Yanyuan: “If we never engage in what seems useless, how can we find joy in this finite life?”

“Chinese painting may appear to be ‘useless,’” GAO explains, “but it builds our way of perceiving the world.” Her course moves beyond the gallery, asking students to see painting as a reflection of humanity itself — how different eras captured emotion, nature, and spirit.

The syllabus traces the story of Chinese art from prehistoric rock paintings to the refined brushwork of the Qing dynasty. “A painting, a life, an era,” GAO reminds her students. “Even a single line can reveal the pulse of an age.”

Among the many ideas that linger from GAO’s lectures, one leaves a lasting impression — liubai, the art of leaving blank space. To her, the “empty” parts of a Chinese painting are never void.

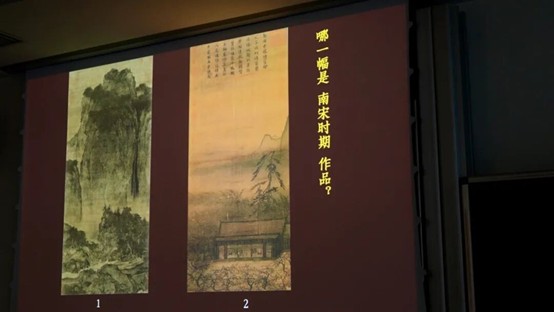

“Blankness is not absence,” she tells her class, displaying Travelers Among Mountains and Streams and Clearing After Snow on a Mountain Pass. “True richness doesn’t come from filling every inch, but from balancing presence and absence.”

Students find this lesson as philosophical as it is artistic. “Liubai taught me that fullness sometimes comes from emptiness, and wisdom from restraint,” says LIN Yixin, an engineering student. “It’s a way to live, not just to paint.”

GAO’s classes are immersive, almost theatrical experiences. She recreates the mood of each artistic era through color, sound, and rhythm. When teaching the Tang dynasty, her slides glow crimson and the classroom fills with music that echoes the grandeur of an empire. For the Song dynasty, the hues fade to moonlight white, the melodies quieten, and serenity settles over the room.

High-fidelity reproductions of masterpieces like A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains are passed around the classroom, inviting students to observe texture and color up close. “The replicas make the paintings real,” GAO explains. “You can sense the artist’s breath in every stroke.”

She even brings in pigments — azurite blue, malachite green — and demonstrates the meticulous grading of color tones used in ancient painting. Students handle brushes of wolf and goat hair, learning how tools shape artistic expression.

Ink, insight, and inner peace

The course culminates in practice. In the final session, students take up their brushes to copy LU Yifei’s floral sketches using baimiao, the fine-line drawing technique. GAO moves among them, adjusting a hand here, guiding a wrist there. Through each delicate line, the students discover what gufa yongbi (“bone method in brush use”) and chenghuai guandao (“purity of mind reveals the Way”) truly mean.

In forty-five minutes, GAO’s students travel through centuries — but what they gain is timeless. They come to see how the old masters found beauty in stillness and meaning in space, how art reflects the rhythm of life itself.

As Professor GAO puts it: “In every brushstroke, we meet both the painter and ourselves. Chinese painting teaches us to look — and to truly see.”

Adapted and translated from the article written by Zhejiang University

Editor: HAN Xiao