Make cancer cells “allergic”! ZJU scientists ingeniously harness mast cells for cancer treatment

Allergies are usually regarded as a nuisance. Sneezing fits triggered by pollen or rashes caused by shellfish reflect an immune system that reacts too fast and too strongly to harmless substances. Yet this rapid and intensive immune reaction has now inspired a novel approach to cancer treatment.

Researchers in China report a strategy that deliberately redirects allergic immune responses against tumors. By training mast cells — the immune system’s key drivers of allergy — to recognize cancer cells as “allergens”, the team has found a way to ignite rapid immune activity inside tumors that would otherwise evade detection.

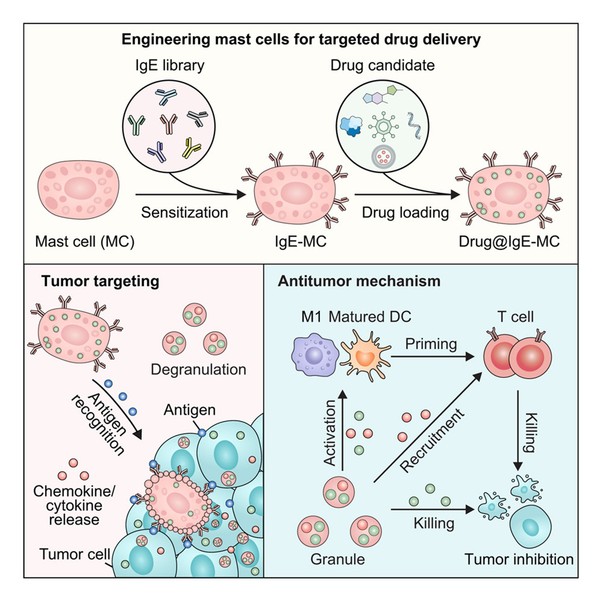

Graphical abstract

The work, published on 10 December in Cell, was led by GU Zhen and YU Jicheng at Zhejiang University, together with LIU Funan at the First Hospital of China Medical University. XU Yan, a postdoctoral researcher at Zhejiang University, is the study’s first author.

Mast cells are best known for their central role in allergic reactions. Distributed throughout the body, they act as rapid-response sentinels, their surfaces densely packed with receptors for immunoglobulin E (IgE). In addition, they store granules loaded with inflammatory molecules inside.

When IgE on a mast cell encounters itscorresponding antigen, such as pollen or shellfish proteins, the cell activates within seconds. It releases its granules, triggering local inflammation and rapidly recruiting other immune cells. This mechanism provides swift protection against threats, but it also underlies allergic disease.

Tumors, by contrast, occupy the opposite end of the immune spectrum. Many suppress immune activity, creating so-called “cold” microenvironments that remain largely invisible to immune attack. The researchers wondered whether these two extremes — allergic overreaction and tumor immune silence — could be linked.

What if the immune system could be forced to overreact inside tumors? The idea was to make cancer cells appear allergen-like, provoking mast cells activation.

To this end, the team coated mast cells with IgE antibodies that specifically recognize tumor-associated antigens. These “sensitized” mast cells were then injected into the bloodstream. When they encountered tumor tissue expressing the target antigen, they became activated immediately.

The effect was dramatic. The mast cells released inflammatory signals that drew immune cells into the tumor, transforming immunologically “cold” tumors into “hot” ones that the immune system could recognize and attack.

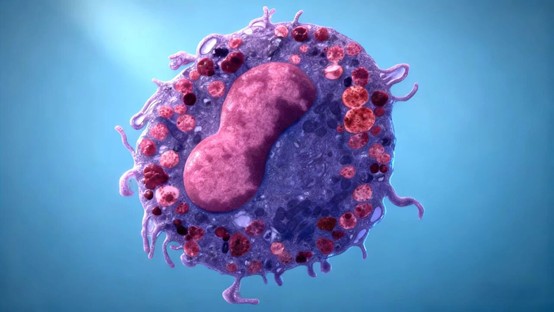

The researchers extended the strategy further by using mast cells as delivery vehicles. The cells were loaded with oncolytic viruses — viruses engineered to infect and destroy cancer cells.

mast cell with oncolytic viruses

Oncolytic viruses face major delivery challenges: when injected directly into tumors, they often fail to reach deep or metastatic lesions; when administered systemically, they can be neutralized by circulating antibodies. Encasing them inside mast cells offered a solution.

“Mast cells act as protective carriers,” said XU Yan. Shielded from antibodies, the viruses could travel safely through the circulation.

Once the mast cells reached the tumor and recognized their target, they rapidly degranulated and ruptured, releasing the viruses locally. The viruses then infected tumor cells, replicated inside them and caused cell lysis. At the same time, mast-cell-derived signals recruited cytotoxic immune cells, including CD8⁺ T cells, creating a combined viral and immune assault.

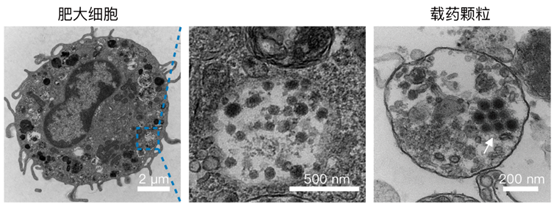

(Left) TEM image of OV@IgE-MC. Scale bar, 2 μm.

(Middle) The enlarged TEM image displaying intracellular OVs. Scale bar, 500 nm.

(Right) TEM image of a granule from activated OV@IgE-MCs. Scale bar, 200 nm.

“Mast cells are not just couriers,” YU Jicheng said. “They amplify the immune response.”

In mouse models of melanoma, breast cancer and lung metastases, the approach significantly slowed tumor growth and increased immune cell infiltration and activation within tumors.

The team also evaluated this strategy in patient-derived HER2-positive tumor models. Tumors shrank markedly, immune T cells accumulated within the tumor tissue, and there were no signs of abnormal blood vessel growth or enhanced metastasis.

A notable advantage of the approach is its flexibility. Because IgE antibodies can be tailored to recognize tumor antigens specific to individual patients, the strategy could be adapted for personalized treatment.

“Each tumor could generate its own ‘allergic signal’,” said GU Zhen. “That opens the door to highly precise, customized immunotherapy.”

The mast-cell platform extends beyond oncolytic viruses. In principle, the cells could carry small-molecule drugs, antibodies, nucleic acids or nanomedicines, offering a versatile framework for next-generation cell therapies.

The researchers are now working to optimize patient-specific IgE screening, scale up cell preparation, and explore how the approach might be combined with existing immunotherapies.

If successful, the work suggests a provocative shift in perspective: allergic reactions, long viewed solely as pathological misfires, may also represent a powerful and adaptable immune weapon — one that cancer researchers are only beginning to harness.

Translator: FANG Fumin

Editor: HAN Xiao